Sam Amidon and Bruce Hornsby & The Noisemakers at Smith Opera House in Geneva, NY on Jun 29, 2019

Bruce Hornsby, the creatively insatiable pianist and singer-songwriter from Williamsburg, Virginia, always has succeeded on his exceptional gifts, his training, and his work ethic. He became a global name in music by reimagining American roots forms as songs that moved with the atmospheric grace of jazz. “The Way It Is” defined sonic joy on the radio, however as a hit record it also evidenced a thrilling re-structuring, and during the years afterward Hornsby, in staggeringly diverse ways, has kept going. He has returned to traditional American roots forms, collaborating with Ricky Skaggs. He has played with the Grateful Dead. He has fused the plunk and dazzle of twentieth-century modernist classical composition to singer-songwriter emotional inquiries. He has scored films. He has performed with symphony orchestras. If the sound of an arrogant air-conditioner or a stretch of rude playing caught his ear, he has entered the hallowed doors of the conservatories of punk. So when Hornsby describes Absolute Zero, his new album, as “a compendium of what I like and moves me,” don’t expect perhaps a thing or two new. Prepare for a multi- faceted ride. A few years ago, Hornsby met Justin Vernon of Bon Iver. “I kept getting these Google Alerts where he shouted me out in the press,” Hornsby says. In time, other musicians praised Hornsby’s work -- including Brandon Flowers, who asked him to play on his solo album. In the indie-rock zeitgeist, Bruce Hornsby became a thing. After Hornsby began working with Vernon, the Wisconsinite invited Hornsby to perform at his Eaux Claires Music and Arts Festival. “I’d played a thousand-and- one festivals over the years,” Hornsby says. “This one was by far the most beautiful experience for me. They had a modern classical stage where you could hear Frederic Rzewski pieces. Everything was artful and beautiful, so great.” Before Hornsby played, The Staves and yMusic appeared. “So I’m listening to this British female vocal trio and Brooklyn chamber music group, going ‘Whoa, who is this?”” Hornsby says. “I loved the women, the chamber music group, the whole thing. What they were doing together was adventurous, a different sound.” Hornsby’s discoveries that evening ultimately circled back to Williamsburg, where over the last years he has hosted his own festival. After Eaux Claires, Hornsby invited yMusic and The Staves to appear at the Williamsburg event. “That’s when I met them,” he says. “We hit it off and became friends. I asked them to play on what became Absolute Zero. We did a session with yMusic in New York. We worked on six pieces; five ended up on the record. It just went from there. yMusic’s leader Rob Moose started doing some things on his own on some new songs that I would write. Rob arranging on his own – where he puts down twenty different string parts (‘Give me another one! OK, there’s that. Another track! Another track!’) – is quite something to see, working his magic in the studio.” The genesis of Absolute Zero, however, began within Hornsby’s work as a film composer for writer-director Spike Lee. Hornsby started collaborating with Lee in 1992; ultimately, in 2008, he began scoring for Lee. Since then Hornsby has written six full film scores and contributed incidental music to four others. What began to intrigue him were scoring components known as “cues,” those comparatively brief passages of music used in films to heighten certain narrative visuals and/or spoken developments. “Over the past decade I’ve written fully 230 different cues,” Hornsby says, “ranging from one to five minutes in length. Through the last ten years of doing this there always were certain cues that sounded like they wanted to be songs, wanted to be developed into something more than just cues, more than just tiny instrumentals setting moods for conversations in a film over dinner, or whatever.” He asked his engineer to make a file of fourteen. Hornsby began working with these Lee cues -- lengthening or shortening or repeating them. “You sculpt and shape the music accordingly,” Hornsby says, “ based on the new information you’ve created over top of these cues.” Then there was the creation of the songs’ lyrics. “For many years, “Hornsby says, “I’ve been interested in literary fiction.” Even in 2019, when literary fiction exists alongside other types of novels and stories, it remains an extensively chronicled and robustly debated kind of writing. Although it was published centuries before rock and roll exploded, literary fiction shares certain values – constant critical scrutiny, for example, as well as absolute freedom on the part of practitioners, even when that sometimes yields some mighty uneasy reading -- with indie-rock. Literary fiction can show up on best-seller lists, just like indie-rock occasionally storms charts. “Like many readers do,” Hornsby says, “I’d dog-ear a page or mark something I thought was well-said, some amazing description of a thimble, say. So I began to think about what for me were the most memorable passages I’d encountered from my reading, the good bits from two writers admire greatly, Don DeLillo and the late David Foster Wallace. On this record, those are my two literary inspirations and guides, Don and Dave.” Hornsby’s songs, both in spirit and memory, function collectively as an hommage to fiction writing that, while often poetic, takes no prisoners. Ready for the results? Those would be pieces like the opening title track -- which features drumming by the legendary Jack DeJohnette -- inspired by DeLillo’s Zero K, a book Hornsby describes as about “the cryonic field – or, most baldly put, Ted Williams freezing in a vault somewhere outside Phoenix.” Or “Fractals,” wherein Hornsby compares a relationship with that “rough and fragmented geometrical shape,” as he puts it, “that can be subdivided into parts.” Or “Echolocation,” a stylistic cousin of “Fractals,” that Hornsby calls “one of my musical combines.” He’s remembering the American artist and pop art instigator Robert Rauschenberg, who during the 1950s made famous hybrids of tactile painting and sculpture, where almost anything, assembled just so rightly, goes. “That aspect of found materials,” Hornsby says, “collages: That’s exactly what my new album is on a musical level. You go into my studio and there’s just crap everywhere – a vibraslap here, a train whistle there, a crappy old violin I’m playing badly. And then there’s my brother playing some dog-shitty violin that’s vibey as hell.” Hornsby produced Absolute Zero, his pastiche of sounds” as it calls the album, with assists from Tony Berg, Vernon, and Brad Cook. Some songs, like “Never in This House,” expose traditional Hornsby songwriting semi-nakedly; others, like “Voyager One” – “sort of chamber art-pop meets Prince,” Hornsby says – and “The Blinding Light of Dreams” – with a groove that Hornsby points out dates back to “Serpentine Fire” by Earth, Wind & Fire – re-stage U.S. r&b as fluidly as the music elsewhere refers to an American modernist composer like Elliott Carter. “Meds,” for example, a particular tour de force of Hornsby/Moose featuring special guitar by Blake Mills, blossoms into gripping ‘60s soul choruses. “Cast Off” manages to animate a rare style – miserablist polyrhythms – without skimping on the funk itself. “White Noise” Hornsby considers “the Wallace moment.” It offers a passionate singer with a string quartet backing him. “The narrative comes from Wallace’s The Pale King,” Hornsby says, “a novel about boredom, about IRS tax examiners as unlikely yet convincing American heroes.” And then “Take You There (Misty),” written with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, concludes the sequence with romanticism as re-ordered by Hornsby via memories of Steve Reich’s and Philip Glass’s sonically floral minimalism. A ride. There is precedent for musical artists moving from the mainstream of popular music to...somewhere else: Ohio-born Scott Walker, ruling the airwaves with The Walker Brothers in early-‘60s Britain, then concocting uniquely dark- toned symphonic solo albums followed by uncharted lands of vocal compositions even much bleaker. David Byrne, determined that the late-70s downtown Manhattan freedom of Talking Heads expand to include pop styles all over the known universe. Robbie Williams, absolutely dead-set on not letting his ‘90s boy- band years preclude pop and rock and swing styles done with uncommon erudition. This stripe of music evolution over time clearly has another member to add to its small and restless club. It’s Bruce Hornsby, a great restructuralist from the beginning and onward. Absolute Zero constitutes absolute 2019 proof. And all you need to hear it is a set of open ears. Bruce Hornsby, the creatively insatiable pianist and singer-songwriter from Williamsburg, Virginia, always has succeeded on his exceptional gifts, his training, and his work ethic. He became a global name in music by reimagining American roots forms as songs that moved with the atmospheric grace of jazz. “The Way It Is” defined sonic joy on the radio, however as a hit record it also evidenced a thrilling re-structuring, and during the years afterward Hornsby, in staggeringly diverse ways, has kept going. He has returned to traditional American roots forms, collaborating with Ricky Skaggs. He has played with the Grateful Dead. He has fused the plunk and dazzle of twentieth-century modernist classical composition to singer-songwriter emotional inquiries. He has scored films. He has performed with symphony orchestras. If the sound of an arrogant air-conditioner or a stretch of rude playing caught his ear, he has entered the hallowed doors of the conservatories of punk. So when Hornsby describes Absolute Zero, his new album, as “a compendium of what I like and moves me,” don’t expect perhaps a thing or two new. Prepare for a multi- faceted ride. A few years ago, Hornsby met Justin Vernon of Bon Iver. “I kept getting these Google Alerts where he shouted me out in the press,” Hornsby says. In time, other musicians praised Hornsby’s work -- including Brandon Flowers, who asked him to play on his solo album. In the indie-rock zeitgeist, Bruce Hornsby became a thing. After Hornsby began working with Vernon, the Wisconsinite invited Hornsby to perform at his Eaux Claires Music and Arts Festival. “I’d played a thousand-and- one festivals over the years,” Hornsby says. “This one was by far the most beautiful experience for me. They had a modern classical stage where you could hear Frederic Rzewski pieces. Everything was artful and beautiful, so great.” Before Hornsby played, The Staves and yMusic appeared. “So I’m listening to this British female vocal trio and Brooklyn chamber music group, going ‘Whoa, who is this?”” Hornsby says. “I loved the women, the chamber music group, the whole thing. What they were doing together was adventurous, a different sound.” Hornsby’s discoveries that evening ultimately circled back to Williamsburg, where over the last years he has hosted his own festival. After Eaux Claires, Hornsby invited yMusic and The Staves to appear at the Williamsburg event. “That’s when I met them,” he says. “We hit it off and became friends. I asked them to play on what became Absolute Zero. We did a session with yMusic in New York. We worked on six pieces; five ended up on the record. It just went from there. yMusic’s leader Rob Moose started doing some things on his own on some new songs that I would write. Rob arranging on his own – where he puts down twenty different string parts (‘Give me another one! OK, there’s that. Another track! Another track!’) – is quite something to see, working his magic in the studio.” The genesis of Absolute Zero, however, began within Hornsby’s work as a film composer for writer-director Spike Lee. Hornsby started collaborating with Lee in 1992; ultimately, in 2008, he began scoring for Lee. Since then Hornsby has written six full film scores and contributed incidental music to four others. What began to intrigue him were scoring components known as “cues,” those comparatively brief passages of music used in films to heighten certain narrative visuals and/or spoken developments. “Over the past decade I’ve written fully 230 different cues,” Hornsby says, “ranging from one to five minutes in length. Through the last ten years of doing this there always were certain cues that sounded like they wanted to be songs, wanted to be developed into something more than just cues, more than just tiny instrumentals setting moods for conversations in a film over dinner, or whatever.” He asked his engineer to make a file of fourteen. Hornsby began working with these Lee cues -- lengthening or shortening or repeating them. “You sculpt and shape the music accordingly,” Hornsby says, “ based on the new information you’ve created over top of these cues.” Then there was the creation of the songs’ lyrics. “For many years, “Hornsby says, “I’ve been interested in literary fiction.” Even in 2019, when literary fiction exists alongside other types of novels and stories, it remains an extensively chronicled and robustly debated kind of writing. Although it was published centuries before rock and roll exploded, literary fiction shares certain values – constant critical scrutiny, for example, as well as absolute freedom on the part of practitioners, even when that sometimes yields some mighty uneasy reading -- with indie-rock. Literary fiction can show up on best-seller lists, just like indie-rock occasionally storms charts. “Like many readers do,” Hornsby says, “I’d dog-ear a page or mark something I thought was well-said, some amazing description of a thimble, say. So I began to think about what for me were the most memorable passages I’d encountered from my reading, the good bits from two writers admire greatly, Don DeLillo and the late David Foster Wallace. On this record, those are my two literary inspirations and guides, Don and Dave.” Hornsby’s songs, both in spirit and memory, function collectively as an hommage to fiction writing that, while often poetic, takes no prisoners. Ready for the results? Those would be pieces like the opening title track -- which features drumming by the legendary Jack DeJohnette -- inspired by DeLillo’s Zero K, a book Hornsby describes as about “the cryonic field – or, most baldly put, Ted Williams freezing in a vault somewhere outside Phoenix.” Or “Fractals,” wherein Hornsby compares a relationship with that “rough and fragmented geometrical shape,” as he puts it, “that can be subdivided into parts.” Or “Echolocation,” a stylistic cousin of “Fractals,” that Hornsby calls “one of my musical combines.” He’s remembering the American artist and pop art instigator Robert Rauschenberg, who during the 1950s made famous hybrids of tactile painting and sculpture, where almost anything, assembled just so rightly, goes. “That aspect of found materials,” Hornsby says, “collages: That’s exactly what my new album is on a musical level. You go into my studio and there’s just crap everywhere – a vibraslap here, a train whistle there, a crappy old violin I’m playing badly. And then there’s my brother playing some dog-shitty violin that’s vibey as hell.” Hornsby produced Absolute Zero, his pastiche of sounds” as it calls the album, with assists from Tony Berg, Vernon, and Brad Cook. Some songs, like “Never in This House,” expose traditional Hornsby songwriting semi-nakedly; others, like “Voyager One” – “sort of chamber art-pop meets Prince,” Hornsby says – and “The Blinding Light of Dreams” – with a groove that Hornsby points out dates back to “Serpentine Fire” by Earth, Wind & Fire – re-stage U.S. r&b as fluidly as the music elsewhere refers to an American modernist composer like Elliott Carter. “Meds,” for example, a particular tour de force of Hornsby/Moose featuring special guitar by Blake Mills, blossoms into gripping ‘60s soul choruses. “Cast Off” manages to animate a rare style – miserablist polyrhythms – without skimping on the funk itself. “White Noise” Hornsby considers “the Wallace moment.” It offers a passionate singer with a string quartet backing him. “The narrative comes from Wallace’s The Pale King,” Hornsby says, “a novel about boredom, about IRS tax examiners as unlikely yet convincing American heroes.” And then “Take You There (Misty),” written with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, concludes the sequence with romanticism as re-ordered by Hornsby via memories of Steve Reich’s and Philip Glass’s sonically floral minimalism. A ride. There is precedent for musical artists moving from the mainstream of popular music to...somewhere else: Ohio-born Scott Walker, ruling the airwaves with The Walker Brothers in early-‘60s Britain, then concocting uniquely dark- toned symphonic solo albums followed by uncharted lands of vocal compositions even much bleaker. David Byrne, determined that the late-70s downtown Manhattan freedom of Talking Heads expand to include pop styles all over the known universe. Robbie Williams, absolutely dead-set on not letting his ‘90s boy- band years preclude pop and rock and swing styles done with uncommon erudition. This stripe of music evolution over time clearly has another member to add to its small and restless club. It’s Bruce Hornsby, a great restructuralist from the beginning and onward. Absolute Zero constitutes absolute 2019 proof. And all you need to hear it is a set of open ears.

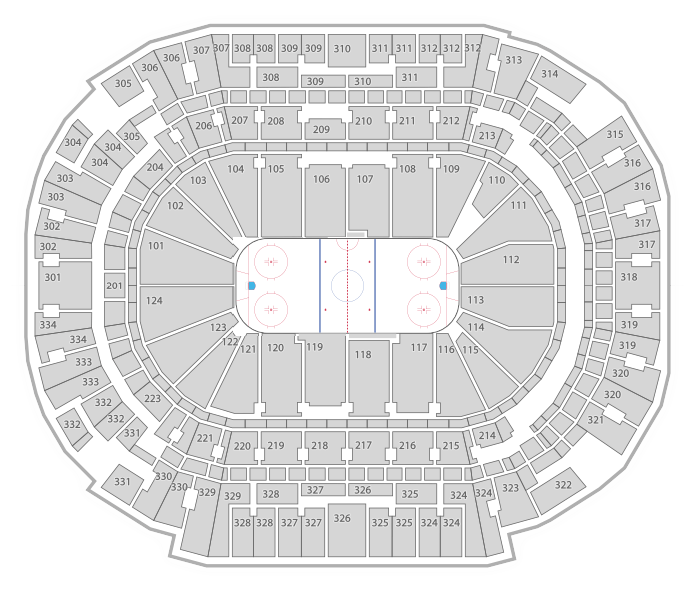

For ScoreBig, use promo code ZUMIC10 for an instant $10 discount. (Cannot be combined with any other offers. Not valid on gift card purchases. Code must be entered at checkout to receive discount.)

The cheapest ticket option is usually the primary ticket seller, but sometimes you can find tickets below face value through secondary ticket sellers. Your tickets are not more expensive when you buy through Zumic, but we do earn a commission from our ticket partners to support our news and concert listings services.